Pain, body, and mind: Relativity of Ego In End Of 20th Century and Beginning Of 21st Century Performative Art.

According to Dietmar Camper, pain and suffering serve as novel experiences that enable the restoration of imaginative functions and an expanded perception of reality. Artistic practices from the later part of the 20th century gave rise to a distinctive language, particularly in the realm of performance art. Camper emphasizes the significance of empathy and active involvement in creating fresh encounters for observers through specific artistic expressions. When exploring the space of performance, the examination of sensory experiences becomes crucial, among which lies the intricate and multifaceted nature of pain. Pain cannot be disregarded as it tends to overpower other sensations and emotions. However, expressing one's subjective experience of pain proves to be immensely challenging. Traditional modes of communication are inadequate in conveying this experience accurately. Understanding someone else's level of pain is nearly unattainable. Performance art emerges as the sole medium capable of projecting pain simultaneously into the visible realm and the sensory domain, creating an imaginable space. Within the context of performance, the artist's body serves as a reference for the experience of pain. Performance art integrates pain into reality, facilitating the acknowledgment of trauma and suffering.

Performance art is, in a sense, a possibility for an artist to use their body and its surroundings as a canvas and the main medium for their practice. The “Body Art Movement” became big in the 70s and flourished from or was inspired by the movement of minimalism. I looked at artists of that time period that incorporated the artist’s body into their performances as the main focus, while delving deeper into the reasons for that to be done. This dissertation endeavors to explore how artists like Vito Acconci, Marina Abramovic, Chris Burden, Ron Athey reacted to the “Body Art Movement”. This dissertation seeks to unravel the nuanced significance behind these artist’s use of the body as a medium.

The “Body Art Movement” started emerging in the 1960’s and reached its peak popularity in the 1970’s. The artists that were related to the movement aimed to disrupt conventional art practices by emphasizing the ephemerality of the body as an artistic medium. The idea of using the body and the ways in which it was utilized ended up confronting societal norms, challenging taboos, and provoking emotional responses from viewers, since the use of the body's image, including naked representation, wasn’t considered a norm at the time. Body Art also had the ability to spark discussions on the body as a site for social, political, and cultural discourse in the context of communicating with the audience. Body art, due to its focus being typically concentrated on the artist himself, typically revolves around gender and personal identity matters. Creators, working with bodily matter, investigate the connection between the physical body and the mind, and showcasing that through performances may involve extreme physical challenges to push bodily limits, playing on the mind's ability to endure pain. Additionally, body art tends to draw the audience's attention by accentuating raw and sometimes unpleasant aspects of the body such as bodily fluids or the concept of nourishment. It explores contrasts related to one’s physical appearance —like between clothed and naked states, isolated body parts versus the complete body. Furthermore, in certain artistic expressions, the body serves as a medium for communication and expression.

To explore the reasons for artists to use their body as a medium as well as ways they used it to convey an idea or build a concept - I chose a list of artists I took an interest in and grouped them depending on the main ideas and similarities of their practice. Vito Acconci and Marina Abramovic both worked on the idea of the relativity of one’s ego and its power. They showcased their perspective on how one views themselves in relation to the society's gaze and how exact an idea of an individual's ego can be when taking these factors into consideration. Both Chris Burden and Ron Athey saw the pain their bodies can experience in different circumstances as a tool for objectification. Even considering that Chris Burden was more focused on body restraints, and Ron Athey placed his interest in the field of self-inflicted violence in social and cultural context, they both pursued a similar idea of pain being an objectifying experience. Bob Flanagan, on the other hand, saw pain as a freeing experience, working his way through his illness with the help of the new-found “tool”. Gina Pane also incorporated pain and violence into her art practice as a performer, however, she would refer to her body as a “sacrifice” for the greater good. In this case - for the messages that she was trying to get through to the public.

Vito Acconci and Marina Abramovic: Ego Relativity And Its Loss

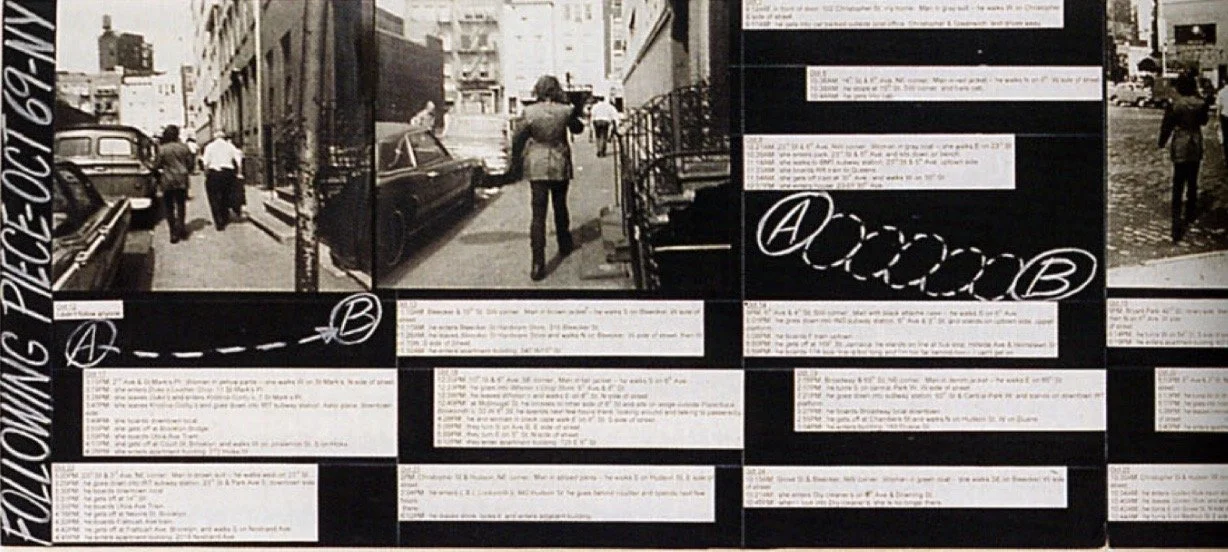

Vito Acconci, The Following Piece, 1969

Vito Acconci was an influential American artist known for his groundbreaking work in the fields of performance art. Acconci gained prominence in the late 1960s and 1970s for his provocative and innovative performance pieces that often pushed the boundaries of art and human behavior in attempts to erase them and tangled the two. In a performance called “Following Piece” 1969, which ponders upon privacy and individuality, Acconci randomly selected people in New York City and followed them until they entered a private space. After this, he would choose a new person to be following. In his notes, Acconci wrote “Following Piece, potentially, could use all the time allotted and all the space available: I might be following people, all day long, everyday, through all the streets in New York City. In actuality, following episodes ranged from two or three minutes when someone got into a car and I couldn’t grab a taxi, I couldn’t follow – to seven or eight hours – when a person went to a restaurant, a movie.” In addition, when planning out the performance, the artist wrote “I add myself to another person (I give up control/I don’t have to control myself)” as one of the bullet points. Vito Acconci conducted this “experiment” in order to strip himself of autonomy, allowing a stranger to dictate his actions. The artist uses his body as a tool for reflecting upon the loss of the artists independance, as showcasing his body traveling in relation to ones of other people is the easiest tool for demonstrating the absence of self-direction or lack thereof. Additionally, Vito Acconci, speaking of the performance, referred to it as a new way of displaying art, which, he said, was similar to a newspaper report. The idea behind it was to overcome a line between the artist and the viewer by getting rid of the stigma behind an artwork, which suggests that it is one unique object.

Vito Acconci, “Airtime” 1973

In “Airtime” 1973, however, Vito Acconci shared a speech on his personal life experience and decisions in order to dissolute his ego - this time, without the absence of selfhood. Acconci spent two weeks seated before a camera directed at his reflection in a mirror. His live image was displayed on a video monitor that was placed in front of a gallery audience. Meanwhile, his voice, conveying a confession, revolving around Acconci's personal five-year romantic relationship with a woman, was sounding within the gallery space. He commented on the motif of the performative act, saying, “I am talking to you so I can understand myself the way you see me.” This phrase touches on the question of dissolving his ego in the idea of relativity of perception when his deeply personal monologue is brought out to the public for interpretation. Vito Acconci, here, is taking interest in how his audience would live through his experience rather than being submerged in it himself. He was interested in passing it onto a group of people as a third party.

Similarly, Marina Abramovic gave herself the right to speak for someone else while being an observer of an action in her and Ulay’s performance “Talking About Similarity, 1976 ” Ulay begins the performative act by facing the audience, then opening his mouth and keeping it agape. While doing so, he was open-mouthed, which called for sucking his saliva out of it, generating an unsettling sound experience for the audience. Ulay then proceeded to sew his lips together with a needle and thread. He pierced his under lip with evident difficulty, then his upper lip, and proceeded to tie the knot.Abramovic, then, stepped in and spoke to the audience as she, unlike Ulay, had the ability of doing so. While explaining the performance, Abramovic adopted Ulay’s persona and was identifying herself with him. She, through Ulay’s character, in first person, explained: “'Because I had open mouth before and by force I close my mouth. That means I can't open anymore by decision.'” Ulay, speaking to Katie O’Dell, an art historian, said that the inspiration behind “Talking About Similarity” partially stemmed from the Baader-Meinhof gang members' actions during their imprisonment in 1972. These individuals looked for a way to demonstrate their opposition, as they were political prisoners. They sewed their lips together to demonstrate how the system would “shut people up” While Ulay sewed his mouth shut, in ignorance of his physical pain, like one do to an inanimate object, he denied himself of autonomy by stripping himself of a choice of opening and closing his lips. As a result of this action, he wasn't longer able to speak. Marina Abramovic explains why she takes it upon herself to speak for Ulay - 'Because the name of the performance is "Talking about Similarity". That means it does not matter who plays which role.' This makes “Talking About Similarity, 1976 ” a product of their symbiotic relationship. While the act of speaking for another person can alter the initial message, this performative act dwells upon the flexibility of the idea of one’s ego and its individualistic autonomy.

Pain As A Tool For Objectification - Chris Burden and Ron Athey

Chris Burden gained his popularity as an artist for his radical and physically extreme artworks. Burden, unlike Marina Abramovic and Vito Acconci, makes his main focus not what a person does to himself, but the impact on his body and choice of imagery themselves. His early and most known performance “Shoot”, staged in 1971, brought him into the spotlight. For this simple performance, Burden arranged to be shot by his assistant with a .22-caliber rifle. From a distance of approximately fifteen feet, Burden was shot in his left arm. The bullet caused a non-fatal injury but created a significant and visceral moment of shock and awe among the audience present. Burden was injured, which caused shock and awe among his audience. Questioning the ethics of art, Chris Burden used his body as a medium, subjecting himself to danger and pain. This way, his body becomes a tool for communication with the audience in an unconventional way, rather than speech and touch.

In a later performance “Fire Roll” 1973, Burden doused his pants in lighter fluid and set them on fire. He extinguished the fire by rolling on the floor and patting himself against it in front of the audience. Here, by subjecting himself to a painful experience, Chris Burden was exploring his body restraints, while pushing the boundaries as far as would be enough for the audience to experience strong emotions from seeing him fabricate a dangerous environment for himself.

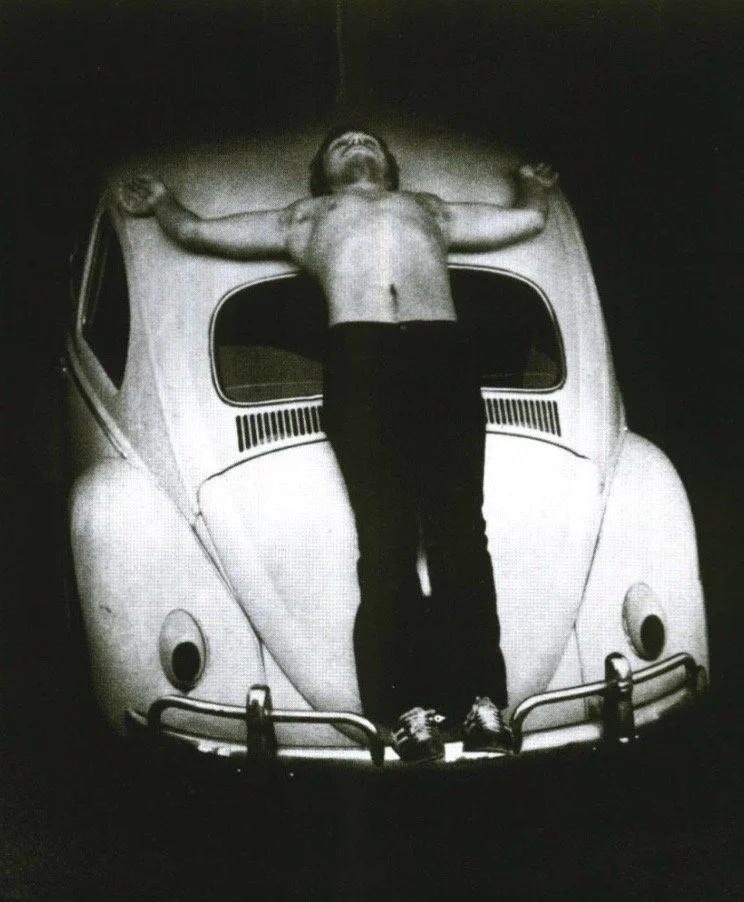

Although, in the context of “Fire Roll”, Burden was able to end his painful experience by the means of his body, in “Trans-Fixed”, he was subject to outer influence that he was not able to influence or escape. Chris Burden was attached to a car - a rear bumper of a Volkswagen Beetle. He was nailed to the car through his palms, in a manner that could be seen as resembling the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. The car with Burden on it was rolled out of a garage and presented to a group of spectators.Considering the status of the can and the religious imagery - this act can be read as a reflection on modern consumerism. In this case, the artist’s fixed pose, bringing him pain, highlights the consciousness of the act as well as portraying the inability to free himself afterwards.

Chris Burden, “Trans-Fixed”, 1974

Another performance, where Chris Burden willingly subjected himself to a painful experience and trapped himself inside of it was a performance named “Through The Night Softly” . Ironically, the action’s nature does not match the title. Burden, wearing only undershorts, had his hands tied behind his back, then laid on his stomach on top of broken glass, scattered around a parking lot. This act of self-inflicted violence was meant to provoke thoughts on the relationship between the artist’s body and the environment it was put in, as well as test its endurance. Showcasing Burden’s pain was not the main subject of the performance. Chris Burden himself commented, “It was shot in black and white. It was real’ abstract - you can’t really tell what’s going on. … It's not really ‘gore-y’. My shoulders get cut, but, you know - it’s all black and white, so it’s not clear what’s going on…” The video evidence aired on November 5, 1973 as a commercial interruption on Channel 9 in Los Angeles and was titled "TV Ad." It was broadcast five times a week for 4 weeks. According to a journalist Nick Stillman - “ … it was aired in a prominent slot just after the 11 pm news. The first three seconds of “TV Ad” are exclusively text — bold letters spelling out “Chris Burden” against a black background, then handwritten script reading “Through The Night Softly” against a gray field.” Burden, famous for airing his performances as TV - commercials, commented on the purpose of this action, saying that they “Stuck out like a sore thumb … I had the satisfaction of knowing that 250,000 people saw it every night and that it was disturbing to them, that they knew something was amiss.” Later, in 1990’s, a performance artist Ron Athey picked up the idea of employing his physical body and pain as a means of artistic expression. His first known performance was executed in 1992 and named “Martyrs & Saints”. Athey, with the help of other performers, went through a series of body modifications such as piercings and incisions. He was carried out for the audience to see him, heavy makeup smeared across his face and his mouth sewn shut with fishing line. After the stitches were removed, Ron Anthey grabbed a microphone and read what seemed to be a manifesto. His speech featured the biblical Lazarus and his personal struggles with being HIV - positive. The idea of mixing religious context, which is usually associated with a more conservative outlook on sex and sexual orientation, which often discriminated against people identifying themselves as something outside of these conservative boundaries, and a monologue about HIV, played with the audience due to its contrast. With blood flowing down his chin and loud music coming from the speakers, his words were barely distinctable. Anthey, unlike Chris Burden, would bring a group of people to create a theatrical experience for the audience. Throughout “Martyrs And Saints'”, he presented a multitude of visuals, including a nurse using a riding crop to strike a woman, himself administering an enema to another man, a man expelling waste into a container, ritualistic piercings leading to bleeding, bondage practice, and a significant presence of Nazi-related items—contrasted with an altar featuring diverse Pentecostal symbols. While Ron Athey worked on this performance with the help of a team, it could still be considered a private act in a public space.

Sex and sexuality, being considered the most private acts in human existence, are lining most of Athey’s practice. “Solar Anus”, staged in 1998, Ron Athey, as part of the performance, showcased his bare anus in the making of a sun tattoo around it. When it was finished, he released a string of pearls from the inside of it. Athey pinned his face and head into a golden crown putting hooks through his skin, he proceeds to self-penetrate, using a dildo affixed to high heels. “Solar Anus” was based on a homophobic essay “L’Anus Solaire”, written by a French sociologist George Bataille in 1931.Bataille describes an erect penis as the sun and the anus as the nighttime, where they are both attracted to each other, but are unable to coexist. With the performance, Athey made an attempt of queering this theory by reversing the positions of the two and ultimately bringing them together in an act of sexual intercourse.

While doing so, Ron Athey went through self-objectification as a means, for, not only did he turn the private act public, but went through a series of painful body modifications and restraints. He openly admits that his practice is partly based on displaying his personal experience as a queer artist, saying, “… it was activism to be who I am, and to represent it in a performance it has to be upped to a hyperreality. So in a way it's really honest, and in another way, it's really manipulative.” Therefore, his performances consisting of both historical content and theatricality and his private rituals are justified.

Physical Pain As A Freeing Experience - Bob Flanagan

Bob Flanagan was an American artist whose main practice was mostly centered around performance art. Flanagan was born with cystic fibrosis, a genetic and life-threatening illness that affects the lungs and digestive system, which came out to be the main reason for him to start an artistic career. Ever since teenagehood, he would engage in acts of self-inflicted violence, keeping it from his family, in order to cope with his physical and mental struggles related to his illness. It was only a matter of time and devotion for his personal S and M practices to grow into performances that were highly personal, and engaged with themes of pain, mortality, illness, and sexuality. Bob Flanagan’s experiences living with cystic fibrosis, the constant pain and countless medical interventions associated with the disease were reasons and, oftentime, subjects of his practice.

Bob Flanagan engaged in a full-time sadomasochistic relationship with his wife, Sheree Rose, where he assumed the role of her slave. Sheree Rose, was highly involved, not only in fulfilling his masochistic tendencies, but in his art career. However, in an interview, she told the audience that Flanagan was not particular about his significant other being involved with his art. In fact, “He always felt like if he had a choice between a mistress and an art career - he would have given up the art career for the mistress if she would have wanted that. But he said he always felt lucky that he found someone who was interested in his art career.” Together, they collaborated across various artistic mediums, including performance, photography, sculpture, text-based art, and video. Flanagan's motto to “fight sickness with sickness” was encapsulated in their collaborative practice, sas well as nuanced play around the term “sick”. Made in 1982, “The Wall Of Pain”, which embodied both an artwork and the outcome of a private interaction. “The Wall Of Pain '' was constructed from 1,800 photographs of Flanagan's face, capturing Rose strucking Bob Flanagan with fifty different objects. For capturing images of Flanagan's face at the moment of impact for each implement, Rose used a shutter-release cable. Each object’s row consisted of thirty-six photographs. Facial expressions in these images depict a mix of agony and ecstasy, which signify the intertwining of pleasure and pain. In most collaborative performances of Flanagan and Rose, they aimed to articulate the experience of illness while asserting control over Flanagan's body. The couple embraced sadomasochism as a way of life, blending together the public and private aspects of it, which is evident in Rose's obsessive documentation of their lives. “The Scaffold” or “Auto-Erotic Scaffold”, put up in 1991, was also a video performance where each part of Bob Flanagan’s body was shot for hours and then assembled into continuous loops, they were then played on seven hanging monitors.

“Auto-Erotic Scaffold” 1991

Each monitor was placed to resemble the actual position of Flanagan’s body parts if he was hung within the gallery walls. The audio edited onto the clips were sounds from films, TV-shows and commercials, which Bob Flanagan gathered himself. Most of the audio footage was either resembling one’s physical pain or talking about it, as well as lectures and monologues about sickness and being unwell. In addition to widely exhibited and known performances of Bob Flanagan, there is some accessible footage of his and his wife’s BDSM practices, which were filmed by Sheree Rose, whose initiative was the pushing element in capturing their private life and sexual intercourse. Some of these videos are featured in a documentary film “Sick: The Life and Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist” made by Kirby Dick in 1997 about Bob Flanagan. “Supermasochist”, through interviews, archival footage, and Flanagan's own discussions, provides viewers with insights into Flanagan's life as a performance artist and someone dealing with a life-threatening illness. Over the course of the documentary’s interviews, Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose speak about their motivations and artistic missions. Footages of Flanagan’s performances, personal archives and monologues are interspersed with him reading poems and singing songs about his relationships and sexual preferences to audiences in stand-up and poetry clubs. His repertoire ranged from songs and poems about his sexual life: “… in which I am beaten, bit, choked, and pinched into a wonderful come… I drink her piss from a baby bottle … she’s on her period and I come out all bloody,” to campfire songs with teenagers in the audience “ … and may your cough always be clear, and may your snot always come out your nose, and not come out your ears.” Regardless of the topic, the general theme of these performances revolved around narrating his own personal life occurrences. “Supermasochist” also features Bob Flanagan creating a sculpture he named “Visible Man”. The “Visible Man” was supposed to mimic Flanagan’s body. The piece is made out of plastic and is a portrayal of a man, providing viewers with a candid view of the human body's inner workings - it shows its internal structures and organs. The body has holes that can be filled with substances that resemble sperm, feces, and phlegm, as Bob Flanagan himself highly identifies with these fluids. This and other sculptures, resembling sickness - related ideas were exhibited at Santa Monica Museum of Art during Bob Flanagan’s performance “Visiting Hours” in 1992.

As the setting for “Visiting Hours”, Flanagan transformed the gallery space and simulated a hospital environment. He designed the space by outfitting it with waiting-room furnishings, potted plants, and copies of “Highlights for Children” magazines, and brought in footage of his other performances and physical art pieces. The installation featured the “Visible Man”, a chest X-ray of the artist's clouded lungs, an arrangement of 1,400 alphabet blocks, creating the initials “SM” (sado-masochism) and “CF” (cystic fibrosis). The room also consisted of depictions of Flanagan’s personal belongings: medical tools, tit clamps, butt plugs, glue guns, and needles. A video installation incorporating bondage scenes sourced from cartoons and films. Amidst the gallery, there was a hospital room, where Bob Flanagan himself was showcased as the focal point. A poem-like text, written by him, was surrounding the walls. There, various inspirations behind his masochism were listed, ranging from childhood encounters with medical professionals and nuns to fantasies of discipline and torture. Describing the ambiance of the room - Karen Alkalay Gut, who saw “Visiting Hours” in 1995, wrote a poem. Lines that feature details of its setting are: “By the time I understood what was going on I was already inside, the little school charts explaining the changes of the body, the x-rays showing the disease and the nipple ring, the toy bin with the superman doll and the leather whip, the blocks with just c/f and s/m letters. C/f for cystic fibrosis, the stomach aches alleviated by the pleasure of masturbation, the pain of a debilitating disease cured by pain controlled, directed, made into art.”

The duration of the “Visiting Hours” was six weeks, throughout which Flanagan was pulled from his bed by a rope and suspended to the ceiling, creating visual evoking notions of departure or transcendence. By committing to this performance act, Bob Flanagan juxtaposed the coexistence of the body's physicality and pain with its poetic resonance. By Flanagan’s bed, there was a hospital radiophone, by which people attending the exhibition could chat with the artist, asking him personal questions about his illness and art questions regarding his practice, which made it a psychologically intimate act, as well as physically. Laura Trippi, a curator, who worked in New York on staging “Visiting Hours” in 1994, said to Los Angeles Times, “Bob’s work was not about bizarre sadomasochistic rituals, but about the possibility of affirming life without denying its dark contradictions.” Agreeing with Bob Flanagan on the idea of battling a painful sickness with being interested in self-inflicted violence, leading to pain, she comments: “He used art as a healing force in his own struggle with CF, and conveyed this to audiences through poems, performances, installations and sculptures of tremendous dignity and wit.” S/M practices themselves could be used in order to play with one's identity and the relativity of it. Engaging in these practices, an individual could brow and reverse and borrow social meanings, as the play is, in a lot of cases, involved with ideas of masters/slaves, children/adults, mothers/fathers/children, etc. “Through its own invention of meaning, S/M reveals that all meaning is invented.”

Body As A Sacrifice: A Higher Purpose

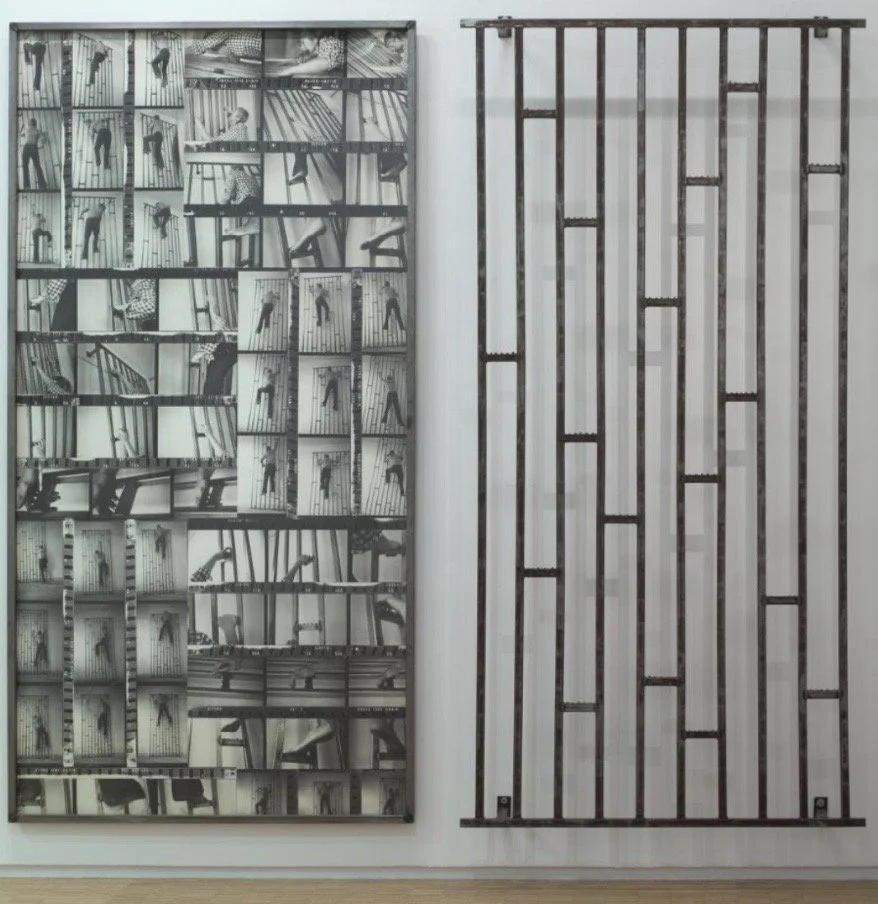

Gina Pane, a French-Italian artist, is best-known for her performances, where she uses self-inflicted violence in order to reflect upon socio-political events. Her path with staging performances, or, as she liked to call them - acts, started in 1971 with “Escalade non-anesthésiée” (“Unanesthetized Escalation”). For the duration of the performance, she would ascend down a ladder with spiked rungs for 30 minutes until her hands and feet were so injured that she couldn't proceed engaging in the action, while her friend, Françoise Masson, was documenting it. Gina Pane stages this action within her studio space, and as the photographic documentation was pre-planned, it captured specific angles to achieve a certain visual impact Pane was going for. Footage of the performance was showcased as an artwork and presented as a diptych: the part on the right featured a collage of close-up images showing Pane's injured feet, while the left side depicted the actual metal staircase utilized by the artist. The approach chosen by Gine Pane showcased not just the visual sequence but also highlighted the physical components highlighting the pain element of the act. The repetition of her hands gripping the ladder and feet stepping up suggested the importance of the passage of time. Gina Pane interpreted “Escalade Non-Anesthésiée'” as a commentary on the Vietnam War, which was a conflict that had endured for 16 years by then, starting in 1955.

Gina Pane, Escalade non-anesthésiée, 1971

She, as an artist, depicted her pain as a form of protest, positioning her body as a sacrificial offering for the purpose of rousing a desensitized society. Pane’s performance artist career started shortly after May 1968 demonstrations, however, she deliberately distanced herself from politically motivated art movements such as Art Sociologique and the Internationale Situationnistes, despite her strong alignment with social critique and political activism. Gina Pane’s performance “Psyche”, which has more to do with self-inflicted violence than creating painful obstacles for an artist’s body, was enacted in 1974. The performative act was staged at the Rodolphe Stadler Gallery in Paris, France and Lasted for twenty-seven minutes and thirty-two seconds. Opening the performance, Gina Pane started applying red lipstick onto a mirror, covering the reflection of her face. Lipstick is a significant symbol due to its symbolic significance as a profoundly feminine object while its shape could represent a phallic symbol. After filling the shape of her face with the lipstick, Pane incised her skin below the eyebrows, by which she overlaid the lipsticked reflection of her and her face covered in blood, which gives the lipstick a new meaning - blood. Her face being blooded, giving it the same colour as the “reflection” then could juxtapose one’s body's senses with the sense of vision. Shortly after, Pane made vertical and horizontal cuts on her navel, which could signify the connection between fetus and mother. In Uta Grosenick's documentation of Pane's works in Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century, Pane describes the stomach incisions as a "Cruciform incision," emphasizing the union of various points in a synthesis of love, intermingling the umbilical cord's time and space with that of the cosmos. Despite Pane’s choice of objects linked to femininity such as the mirror and red lipstick, Pane's intention wasn't to reinforce femininity, but to make it so these elements invert meaning because the image that they are applied to is mirrored. I perceive the imagery presented by Pane as a semiotic showing and communicating with the audience on a level of conveying an idea existing in a cultural and historical context, rather than translating personal issues. Compared to Bob Flanagan and Ron Athey, whose performative careers were mostly built upon their life experiences (where Athey brings some religious imagery into his practice), Gina Pane works with the audience in the ideological and societal plains. Pane herself refers to her reasons for the use of her body as a medium saying, “My body experiments proves that the ‘body’ is occupied and shaped by society.”

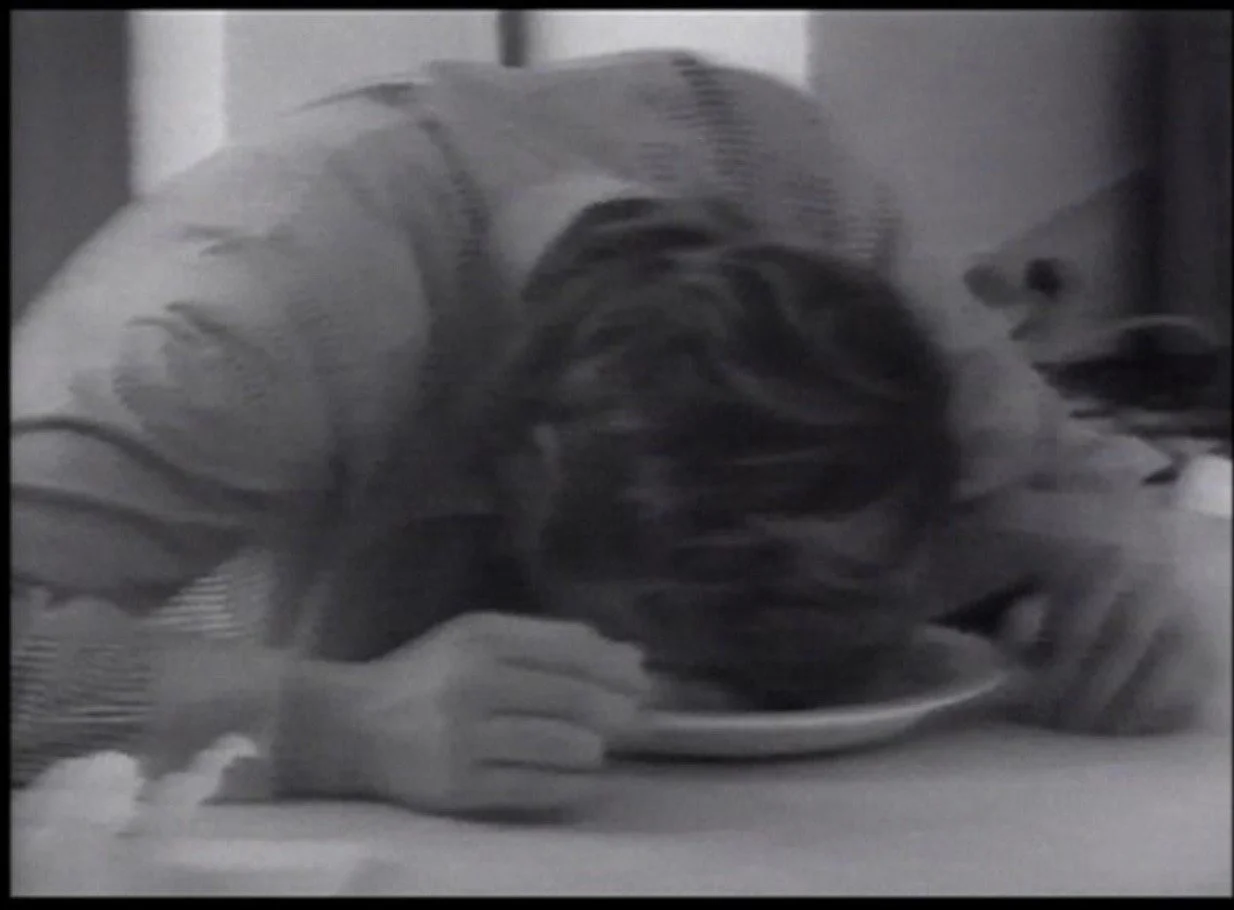

In 1971, during a performance “Nourriture, actualites televisees, feu” (“Food/TV News/Fire”, Gina Pane used her body to consume raw ground beef under the glare of a strong light, regurgitating it, while observing news coverage of the Vietnam War on a TV. The idea of doing so was confronting her repulsion and condemning the violence inflicted upon the animal. All this done while seated uncomfortably, which hints to the artist’s general dissatisfaction with the setting. Additionally, she put out fires on the sand with her bare feet until the pain became intolerable and Pane couldn’t withstand the action anymore. Her performance was also broadcast on another television screen to prompt the audience to realize the significance of the screen. Despite her previous experience with the act of incision using a razor blade, which was symbolic of her engagement with pain, the actions during this event didn't directly refer to that injury. The action unfolded in three distinct moments, almost forming a narrative sequence: first, consuming raw minced meat from a bowl without any utensils; then, watching the day's television news while facing the visual disruption caused by a glaring light bulb placed at eye level; and finally, extinguishing small fires fueled by burning alcohol with her hands and feet on sand. The invitation for the event specifically stated that a minimum of 2% of each attendee's monthly salary should be deposited in a safe at the venue.

Gina pane, Action Nourriture/Actualités télévisées/Feu, 1971

The event served as a reminder that art cannot exist as an entirely free act, preceding the extended consumption of 600 grams of meat until the disgust of it echoed Georges Bataille's reflection: "He who eats the flesh of another animal is his fellow." This act of abrupt ingestion in some way reinstated the cruelty associated with living beings. Eating directly from the dish, close to the raw and unprocessed meat's pungent smell, compelled the artist to confront the image of lifeless flesh, akin to her own carnivorous nature. Toward the conclusion of the action, Gina Pane found it unbearable to roll the meat between her fingers, as the ingestion had disrupted the typical passive relationships associated with nourishment. Possibly influenced by McLuhan's theories outlined in "Television in a New Light," which suggested that the primary aim of television images was to stimulate spectators' sensitivities and that communication means altered our sensory equilibrium, Pane's deliberate pause in front of concerning news images on that evening refuted any avoidance of political and social realities of that time. Simultaneously, it conditioned the audience to view images beyond the conventional vision, measuring them against one's own bodily unit. Her proximity to the screen and resistance to the dazzling optical effects aimed at reclaiming information in a critical manner, bypassing theoretical elaboration. Positioned close to the lit light bulb, her posture forced her to confront the limits of physical endurance in order to exercise her freedom as a viewer: to perceive and comprehend despite societal attempts to control the body. I could argue that among artists of her generation, none had translated bodily expression into a language as concise and symbolically potent as Gina Pane and Ron Athey did.

-

The exploration into the world of performative art across the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century provides one with innovative and diverse expressions of personal issues and ways to speak to the public. Artists like Vito Acconci, Marina Abramovic, Chris Burden, Ron Athey, Bob Flanagan, and Gina Pane, provided me and other upcoming artists and students with a spectrum of experiences, ranging from the dissolution of individuality to the use of pain as a means of communication and self-expression. All that done with their body as the main medium, prompted them to be creative while preserving the simplicity of using just one object, which was themselves. Vito Acconci's pioneering performances challenged the concept of autonomy and privacy. In his performance named "Following Piece", Acconci had to gain enough bravery to actually be able to follow people, not letting societal standards of behavior limit him. He also proposed a new way of exhibiting work, by which he inspired me to drift away from standard artwork organization into annotating my work on the spot when showing. His performance piece “Airtime”, which dwells upon the idea of privacy of speaking to self, almost shows a process of showcasing day-to-day life, which inspires me with its simplicity and it being able to engage with the audience Acconci's performances involve sharing deeply personal experiences and using them as a catalyst for questioning the essence of ego and the relativity of its perception.

Marina Abramovic, in her collaboration with Ulay, looked at the idea of boundaries of individuality and representation when Marina spoke for Ulay keeping her own voice in “Talking About Similarity, 1976.” I was surprised by the way Marina Abramovic and Ulay transformed a prison “strike”m where prisoners were using imagery of a sewn mouth to convex the idea of them being silenced into a performance on the relativity of identity. They showed the issue as if it does not actually matter who speaks as long as the message was being conveyed, but, most importantly, they made it out so the audience would question their outlook on the action.

Chris Burden's artworks could be seen as more radical. In “Shoot”, for instance, due to the use of a firearm, which is usually associated with deadly danger and major health complications more than sharp objects or direct physical violence. “Fire Roll” uses fire, which is, in a lot of cases, an uncontrollable “substance” and could be seen as a more dangerous impact than the ones that I have listed before. "Trans-Fixed," pushed the envelope by subjecting himself to extreme pain and physical risk, inviting audiences to witness and question the limits of the human body and its endurance. Ron Athey continued this exploration of pain and self-inflicted violence, utilizing his performances to highlight issues of sexuality, societal taboos, and personal experience, as seen in "Martyrs & Saints" and "Solar Anus." Ron Athey, though, unlike Burden, uses external references such as religion and old essays, which, to me, stands out as a deeper message. He uses his body to stage and recreate religious imagery in order to reflect on his position in society and speak to the audiences' associations using pain to objectify himself in the realms of already existing settings.

Bob Flanagan's life with cystic fibrosis led him to use pain and masochism first as a personal coping mechanism and then as a medium for artistic expression. His collaborations with his wife, Sheree Rose depicted both the physical aspects of pain in performances like "The Wall of Pain" and "The Scaffold" and delved into the intimacy of their relationship and the intertwining of pain, art, and life. Bob Flanagan also sought inspiration in his personal life. He also looked for people that would understand where he was coming from and relate to his issues at least on the level of interest and compassion.

Gina Pane's performances I spoke about, such as "Escalade non-anesthésiée" and "Psyche," reflected engagement with self-inflicted violence as a symbolic act of sacrifice. Pane's art aimed at evoking societal responses and engaging viewers with her confrontational stance on political and social issues, using her body as a tool for commentary. Gina Pane used her body to invoke a reaction in the audience and provoke thoughts on the matters of social and cultural issues, rather than her identity struggles. She, I could say, used her body as a symbol more than as her personal property. She didn’t associate her performative actions directly with her personal life

The narratives of these artists all include pain, sacrifice, and the dissolution of individuality, where their body is used to serve as a tool for expression, communication, and societal/political critique. The listed performances highlighted not only personal experiences but also societal taboos, political struggles, and the power dynamics inherent in human existence.

References and bib:

Abraham, A. (2014) Ron Athey Literally Bleeds For His Art, VICE. Available at: https://www.vice.com/en/article/vdpx8y/ron-athey-performance-art-amelia-abraham-121.

Alkalay-Gut, K. (1998) ‘Ode to Bob Flanagan’, Disability, Art, and Culture (Part Two), xxxvii(3).

Arn, J. (2023) The Man Who Hurt himself for art, The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-art-world/the-man-who-hurt-himself-for-art-chris-burden.

auto-erotic scaffold/sick (no date). Los Angeles.

Bataille, G. (1931) The Solar Anus, The Anarchist Library. Available at: https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/georges-bataille-the-solar-anus.

Berest, V.A. (2020) Anthropology of Pain in Gina Pane’s Performances: From Sacred Tradition to Provocation. dissertation.

Boyer, E.J. (1996) Bob Flanagan; Artist’s Works Explored Pain [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-01-09-me-22683-story.html.

Chris Burden - Through the Night Softly (2011). Laguna Art Museum. 27 October. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OB6gg1i2hc8.

Delivery, P. (2019) Chris Burden’s trans-fixed – crucified on a Volkswagen, Public Delivery – Art non-profit. Available at: https://publicdelivery.org/chris-burden-transfixed/.

Flanagan, B., Rose, S. and Rugoff, R. (1995) ‘Visiting hours’, Grand Street, (53), p. 65. doi:10.2307/25007885.

Gina Pane Art, Bio (no date) The Art Story. Available at: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/pane-gina/.

Gonzenbach, A. (2011). Bleeding Borders: Abjection in the works of Ana Mendieta and Gina Pane. Letras Femeninas, 37(1), 31–46.

Johnson, D. (2015) Pleading in the blood the art and performances of Ron Athey. London: Live Art Development Agency.

Krauss, R. (1976) Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/778507.

Levin, T.Y. (2002) CTRL space: Rhetorics of surveillance from Bentham to big brother: Karlsruhe, ZKM - Center for Art and Media, 12 October 2001 - 24 February 2002. Karlsruhe: ZKM Center for Art and Media.

Macdonald, L. (2003) BRING THE PAIN: Bob Flanagan, Sheree Rose and Masochistic Art during the NEA Controversies. Dissertation.

McMahon, J. (no date) Vito Acconci’s Following Piece.

O’Brien, M. (2014) Performing chronic: Chronic illness and endurance art.

O’Dell, K. (1998) Contract with the skin masochism, performance art, and the 1970’s. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Richards, M. (2009) ‘1’, in Marina Abramovic. London: Routledge.

Riedel, T. (2005) ‘art since 1900: Modernism, antimodernism, postmodernism. Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, Benjamin Buchloh’, Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 24(2), pp. 59–59. doi:10.1086/adx.24.2.27949380.

Sandahl, C. (no date) ‘Bob Flanagan: Taking It Like a Man’, in. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/162641507.pdf.

Sargent-Wooster, Ann. "CBTV: Video by Chris Burden." Performing Arts Journal, vol. 5 no. 6, 1982, p. 90-94. Project MUSEmuse.jhu.edu/article/655592.

Schulze, Martin (13 September 2023). Some of Vito Acconci’s most influential performance pieces, https://publicdelivery.org/vito-acconci-performances/.

Scott, I. (2019) Gina Pane Made a Spectacle of Female Suffering as a Form of Protest, Frieze.

Stillman, Ni. (2010) Do you believe in television? Chris Burden and TV, East of Borneo. Available at: https://eastofborneo.org/articles/do-you-believe-in-television-chris-burden-and-tv/.

Talking About Similarity (1976) LIMA . Available at: https://www.li-ma.nl/lima/catalogue/art/ulay-marina-abramovic/talking-about-similarity/1833.

Tate (1968) Body art, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/b/body-art.

Voss, K. (2014) Valie Export, Gina Pane, and Orlan: Pain, Body Art, and the Question of the Feminine. Dissertation.

Ward, Frazer. “Gray Zone: Watching ‘Shoot.’” October, vol. 95, 2001, pp. 115–30. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/779202.

Wessendorf, M. (1995) Bodies in Pain: Towards a Masochistic Perception of Performance — The Work of Ron Athey and Bob Flanagan, Bodies in pain. Available at: https://www2.hawaii.edu/~wessendo/Bodies%20in%20Pain.htm.

-

Anderson, C.A. and Bushman, B.J. (2018) “Media violence and the general aggression model,” Journal of Social Issues, 74(2), pp. 386–413. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12275.

Bray, X. and Payne, E. (2018) Ribera Art of violence. Lewes: GILES.

Canvin, Y. (2007) Aftershock: Conflict, violence and resolution in contemporary art published on the occasion of the exhibition held at Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 14 July - 2 September, 2007 ; University of Hertfordshire Galleries, 20 September - 28 October, 2007. Norwich: Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts.

Fraser, J. and Koppel, T. (2002) Violence in the arts. Livonia, MI: Schoolcraft College.

Melović, B. et al. (2020) “Research of attitudes toward online violence—significance of online media and social marketing in the function of Violence Prevention and Behavior Evaluation,” Sustainability, 12(24), p. 10609. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410609.

Prince, S. (2006) “Beholding blood sacrifice in the passion of the christ,” Film Quarterly, 59(4), pp. 11–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2006.59.4.11.

Trend, D. (2007) The myth of media violence : a critical introduction.

Waddell, F., Bailey, E. and Davis, S. (n.d.) Does Elevation Reduce Viewers’ Enjoyment of Media Violence?: Testing the Intervention Potential of Inspiring Media, APA Psych Net.

Contract with the Skin: Masochism, Performance Art, and the 1970s, Kathy O’Dell

Gough, R. and Roms, H. (2002) On archives and archiving. London: Routledge.

Tate Modern ‘No Lone Zone’

Teresa Margolles “In the Air”

The Function of Masochism in Performance Art of the 1970's: A Psychoanalytic Examination of Performances by Chris Burden, Marina Abramović, and Abramović/Ulay, Philip W. Chang

The Aesthetics of Violence : Art, Fiction, Drama and Film, Robert Appelbaum

Beck, A. (2003) Cultural work: Understanding the cultural industries. London: Routledge.

(No date) Marginalization | english meaning - cambridge dictionary. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/marginalization